Written by Leeroy Ting & edited by Deborah Woong

In early December 2015, Mohamad Zulkifli Ismail was charged with Murder for stabbing two men who tried to rob him at his house, killing one of the men in the process. This case was particularly haphazard as it resulted in huge public uproar and a tsunami of misinformation that has caused much confusion to spread among Malaysians. For example, the mistaken notion that comparing knife sizes is somehow important when it comes to self defence.

As such, we at Vox Malaya feel obligated, as law students who had the privilege of acquiring knowledge about this area of law, to do what we can to clear the massive fog of fear and doubt that has come to envelop the issue of self defence as it is a fundamental knowledge that should be equipped in every citizen’s legal arsenal.

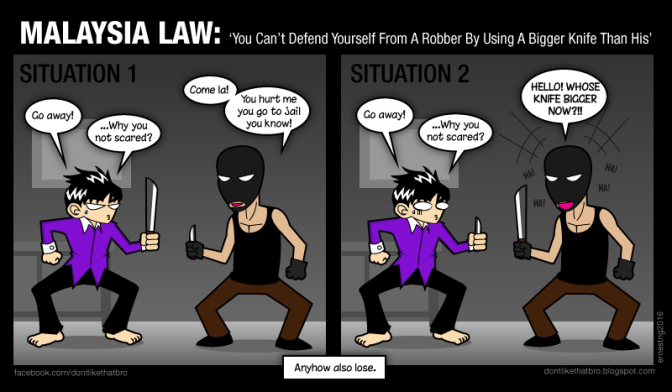

An example of the misconceptions that arose regarding self defence. (Comic from dontlikethatbro.blogspot)

What is Self Defence?

The law of private defence establishes that a person who is attacked is justified in law to retaliate and to mount a counter attack provided that the injury he inflicts is proportionate to the injury which he was threatened with. This principle is embodied in section 96 of our Penal Code.

The meaning of private defence is further explored in section 97 which states that every person has the right to 2 forms of private defence; (a) the right to protect oneself and others from physical harm (b) the right to protect one’s property from harm.

Private Defence of Person

Section 100 of the Penal Code states that in exercising private defence, one can retaliate to the point of causing death to the assailant when it involves; (a) apprehension of death (b) apprehension of grievous hurt (c) intention to rape (d) intention to gratify unnatural lust (e) intention to kidnap or abduct (f) intention to wrongfully confine.

Section 101 states that in all other circumstances, it is only acceptable that one voluntarily harms the assailant without causing death.

However, there is an important condition to fulfill before this defence can be raised. Section 102 states that one can only raise the right of private defence when there is a reasonable apprehension of danger, and that right persists so long as the threat exists.

This can be seen in the landmark case of PP v. Dato Balwant Singh. In that case, the deceased was a road bully who followed the accused’s car after he got enraged thinking that the accused honked at him. When the accused pulled into a mosque, the deceased picked up a large and heavy stick and threatened the accused with the stick. Even after the accused showed the deceased his gun and fired a warning shot, the deceased did not relent and continued to act even more aggressively. Fearing for his life and safety, the accused fired his gun and caused the death of the deceased.

The court held that the right of private self defence commences as soon as there is a reasonable apprehension of harm to the body, the act of private defense should not exceed what is reasonably necessary to avert the assailant’s attack and lastly, a man does not need to wait for his assailant to strike the first blow before defending himself. As such, the court found that the right of self defence under s. 97 & s. 100 of the Penal Code applied as the deceased had a large stick that was sufficient to cause grievous harm, refused to back down even after the accused fired a warning shot and there was a reasonable apprehension of bodily harm to the accused.

As we can see from the above case, the court held that the right of private defence applies even though the accused used a gun against the deceased who was armed with a large stick. Therefore, the idea that one cannot fight a robber with a larger knife than the robber is clearly misconceived.

The type of weapon used is not as important as the existence of a reasonable apprehension of death or grievous harm (Picture credit: 9gag.TV)

The Malaysian stance on the right of private defence to body is further clarified in the case of Musa bin Yusoff v. PP. In this case, the accused was involved in a fight where the deceased attacked the accused with an iron bar. In the course of the fight, the accused managed to wrest the the iron bar from the hands of the deceased and used it to kill the deceased. At the High Court level, the argument of private defence was unsuccessful as the deceased was unarmed at the time of death. As a result, the accused was convicted for culpable homicide.

However, in an appeal to the Court of Appeal, the decision was overturned. The Court of Appeal held that the law in Malaysia is that a man who is assaulted is not bound to modulate his defence according to the attack, before there is reason to believe the attack is over. He is not obliged to retreat, but may pursue his adversary until he finds himself out of danger. And if he happens to kill in the conflict, it is justifiable even if his actions might seem a little excessive to a perfectly cool bystander. As a result, the court found that the accused did not exceed the right of private defence as he was preventing the possibility of a renewed attack onto himself.

Therefore, the question to be used in Malaysia in such cases will be whether there was a reasonable apprehension of such danger, not whether there was an actual continuing danger. The law in this country gives greater latitude to a person who is attacked. He is not required to stop before there is reason to believe that the threat from the attacker is over.

Right of private defence of third party?

The right of private defence also extends to the protection of a third party. This can be seen in the Federal Court case of Wong Lai Fatt v. Public Persecutor where the court held that the accused, who had used a knife to kill a man who was raping his wife, was justified by section 100 of the Penal Code to do so. As such, the court ordered the release of the accused.

The right to self defence also extends to the protection of 3rd parties

Private Defence of Property

The right to private defence also extends to defence of property as provided for by s. 97(b).

Section 103 states that the right of private defence of property even extends to causing death to the wrong-doer if the offence constitutes (a) robbery (b) house breaking by night (c) mischief by fire (d) theft, mischief or house trespass. These offences must reasonably cause apprehension of death or grievous hurt.

However, section 104 states that in any other circumstances, it is only acceptable that one voluntarily harms the assailant without causing death.

When does the right of self defence of property commence and end?

In the Court of Appeal case of Salahuddin Orah v. PP, the deceased had destroyed vegetables on an oil palm plantation belonging to the accused. An argument ensued and 3 days later, the accused killed the deceased with a parang. The learned trial judge held that for the right of private defence of property to apply, the Appellant’s reaction to the deceased’s act must be spontaneous and commensurate with the destruction of his property. However, in the present case, three days had elapsed between the destruction of the vegetables and the reaction by the Appellant. The right to defence of property thus do not apply.

As we can see from the above case, just because one’s property was harmed, it does not grant an absolute and perpetual license for the victim to enact revenge or take actions of self defence. As such, it is important to know when does the right of self defence of property commence and ends.

No, you cannot do this in Malaysia.

Fortunately, such information is laid down in section 105 (1) – (5) of the Penal Code;

(1) Danger to property – The right to private defence of property commences when there is a reasonable apprehension of danger to the property.

(2) Theft – The right continues until the offender escapes, or the assistance of the public authorities is obtained, or the property has been recovered.

(3) Robbery – The right continues as long as the offender causes or attempts to cause any person death, hurt, or wrongful restrain, or as long as the fear of such possibilities continues.

(4) Criminal Trespass/Mischief – The right continues as long as the offender is in the act of either criminal trespass or mischief.

(5) Housebreaking by night – The right continues as long as the act of housebreaking persists.

As we can see from the qualifications in S. 105 (1) – (5), many of the circumstances where self defence applies are reactionary, spontaneous and in parallel with the offending act. As such, one cannot pursue a housebreaker or robber who has fled from one’s house and hurt him on the streets because the time limit for the right of self defence of property would already have ended. In such circumstances, one’s only recourse would be the public authorities.

Additional Restrains on the right of private defence

Besides the condition that there must be a reasonable apprehension of death or grievous harm and the reaction must be impromptu and immediate to the offence, there are 2 further frequently invoked conditions onto the right of private defence;

- Time to resort to the protection of public authorities (Section 99(3))

Section 99(3) States that no private defence can be raised when there is time to have recourse to the protection of public authorities.

In the above cited case of Salahuddin Orah v. PP, another reason the learned trial judge held that the right of private defence of property did not apply would` be the fact that the accused, upon discovering the destruction of his vegetables, had ample time to make a police report against the deceased but he did not do so. As such, the restriction in s. 99(3) of the Penal Code barred the accused’s defence.

From this case, we can see that the right of private defence would only be permitted if a victim had no opportunity to resort to public authorities and had no choice but to exercise an act of self defence.

Sometimes calling the cops is still your best bet (Picture source: AFP)

- The restrain of proportionality (Section 99(4))

Furthermore, s. 99(4) of the Penal Code states that in the exercise of the right of private defence, no more harm than necessary is to be inflicted.

This principle can be seen in the case of PP v. Halim Din. In this case, JAKIM officers armed with sticks, ambushed the accused, a policeman, at a house of his lady friend. The accused while running away from the officers, opened fire at the pursuers causing one to die. The accused alleged that he thought the officers were gangsters who were after his life despite witnesses testifying that the JAKIM officers had loudly identified themselves beforehand.

The court held that the right to self defence did not apply in the above case as on the weight of evidence presented, the accused clearly knew that the JAKIM officers did not constitute a threat to his life. However, the court also held that even if the right to self defence applied, he had exceeded his right of self defence as the men was only armed with pieces of wood and cangkul and was separated from him by a fence at the time of the attack and thus could not be a danger to his life which justified the use of a gun. The court therefore convicted him of culpable homicide.

This shows that when it comes to self defence, the principle of proportionality is important and when there is no risk of death, it is unjustified for a person acting in self defence to inflict death onto an attacker.

Disproportionate Self Defence (Picture credit: stlewis.blogspot)

Application – Facts of the case

After understanding the principles of self defence, let us attempt to apply it to a hypothetical situation that is similar to the statement given by Zulkifli to the police. One should keep in mind that this is Zulkifli’s version of the events and not a result of the police’s investigations so the facts of the actual case might be different.

Malaysian hero? Zulkifli has garnered a lot of love & support among Malaysians

According to a report by Malaysian Insider, Zulkifi lives in a part of town that has frequent break-in cases. Because of this, Zulkifli and his family are always on high alert. On the day of the incident, Zulkifli’s wife saw two men on a motorcycle riding up and down the streets in front of her home suspiciously while she was at her stall, which was 300 meters away. Zulkifli’s wife then alerted Zulkifli who was also at the stall with her.

Zulkifli quietly sneaked up on the two men when they stopped the motorcycle in front of his home and saw one of the men trying to dislodge the generator of his house’s auto-gate while the second man stood guard on the motorcycle. Suddenly, the man on the motorcycle saw Zulkifli and charged at him with what was believed to be a steel rod and tried to strike him down.

Zulklifli immediately took out a small blade he brought along and stabbed the man who lunged at him. The second robber, who saw the whole thing, lunged at Zulkifli too but Zulkifli managed to stab the man near his shoulder. The first robber hopped on to his motorcycle and got away. The second robber tried to catch up with the first robber but collapsed and died near the scene of the incident. Zulkifli then turned himself in to the Police later that day.

Application of laws

Zulkifli would most probably be charged with s. 304, culpable homicide not amounting to murder as opposed to murder under s. 302. This is because an essential element of murder, the mens rea or intention to kill did not exist in the present case. This can be seen in the case of PP v. Halim Din where the Court of Appeal reduced the charge to culpable homicide as they found that there was no evidence that the respondent intended to murder anyone. Similarly, in the current case, the mens rea to murder cannot be inferred from Zulkifli’s act of stabbing as one robber was stabbed in the shoulder and the other survived long enough to attempt to cross the road. As such, the strikes do not seem to be meant to be fatal.

Now that we have identified the more suitable charge, we now come to the question of whether there are any applicable defence, namely, the right of private defence under s. 97 & s. 100. In the case of PP v. Balwant Singh, the court found that the right to private defence arose as the deceased was swinging at the accused with a thick branch which was “big enough to cause a person’s skull or bones to crack if hit with it”. The accused, therefore was justified in taking the second shot which caused the death of the deceased. Similarly, in the present case, there was a high chance that the right of private defence would be applicable to Zulkifli as the deceased lunged at him with an iron bar, a weapon that is arguably more deadly compared to the thick branch used in Balwant Singh. Furthermore, the deceased lunged at the accused after he witnessed them in the act of committing a crime and therefore it is reasonable for one to have a reasonable apprehension of death or grievous hurt as a criminal would often want to kill or incapacitate witnesses to their crimes.

Furthermore, unlike the case of Salahuddin Orah v. PP, Zulkifli did not have time to recourse to the protection of public authorities as when he followed the two robbers back to his house, it was mere unrealized suspicion and would be too premature to call the police and by the time he saw the crime, it was too late as the robbers lunged towards him thus putting his life in danger. So the limitation of s.99(3) should not apply.

Lastly, unlike the case of PP v. Halim Din, where it was a gun versus a piece of stick, the limitation of proportionality under s. 99(4) also should not apply as the deceased was armed with an iron bar while Zulkifli defended himself with only a small knife. Besides that, the robber was also lunging towards Zulkifli and at a close enough proximity to hurt him unlike the case of Halim Din where they were separated by a fence.

In conclusion, in my humble opinion, Zulkifli might be charged with s. 304, culpable homicide not amounting to murder but he stands a high chance of being acquitted if the court finds that his actions were justified by s. 97 and s.100, the right to self defence of body.

Conclusion

The death of a human being is a horrible tragedy that should be avoided whenever possible. As such, citizens are not encouraged to take the cause of justice into their own hands. The state should only bestow the right to kill another human being to citizens only when absolutely necessary. Thus many restrictions and conditions are imposed onto the right of self defence to prevent the act of murder from being taken lightly.

As such, it is important for citizens to realize that self defence is not equivalent to a license to kill and should only be exercised when there are no other options available or they too, like the perpetrator, will rightfully face the full brunt of the law as an act of murder done in the throngs of passion for revenge is no less heinous than murder done for personal gain and thus must be judged similarly in the objective eyes of the law.

To understand the principles of self defence would equip us to prepare for such situations and know of the right thing to do when circumstances arise to prevent us from becoming the monsters we seek to fight.

This is Kylo Ren. He was consumed by hatred and a thirst for revenge. Don’t be like Kylo Ren. (Picture credit: Blastr.com)

this is a very good explanation indeed. thank you. unfortunately, i dont think people who likes to critics legal system in malaysia would read this. in fact, i dont think they like to read. still, this is a very useful indeed. nice!

LikeLike

thanks for the information.

LikeLike

please, to express, the case’ citations

LikeLike